Celebrating Nowruz the Central Asian way

Framed by the snowy peaks of the Tian Shan mountains on the southern horizon, two teams of horsemen gather at centre field in Bishkek’s Ak-Kula Hippodrome to compete in the championship match of Kyrgyzstan’s national sport, kok-boru.

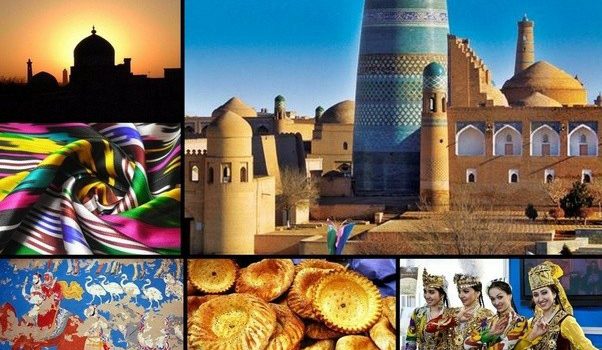

In a scene that plays out with small variations across the major cities of Central Asia each March, celebrations for the traditional Nowruzholiday – Central Asia’s largest – begin early with horse games, performances and picnics and last late into the night with pop concerts and fireworks displays. Nowruz is typically celebrated on 20 or 21 March, though dates vary each year.

Traditional dancers perform in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan during Nowruz © Anadolu Agency / Getty Images

Traditional dancers perform in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan during Nowruz © Anadolu Agency / Getty Images

While western celebration of the holiday is a relatively recent phenomenon (UNESCO listed it as ‘Intangible Cultural Heritage’ in 2009), Persian tradition holds Nowruz (literally “New Day” in Farsi; also Navrus in Uzbek, Nauryz in Kazakh, Novruz in Turkmen, Nooruzin Kyrgyz and Nauroz in Dari) to be a 15,000-year-old celebration of the end of winter and the start of a new year and new harvest cycle.

Modern celebrations in the region forego the traditional feasts of Iranian homes in favour of national sports, public spectacles and more than a bit of vodka to see the old year out and the new year in.

History of Nowruz in Central Asia

Originally a Zoroastrian harvest festival later subsumed into the Persian calendar, Nowruz was most likely introduced into Central Asia during the Achaemenid era (c. 550–330 BC). The ongoing popularity of the holiday across Central Asia is one of many indelible remnants of the empires that variously ruled this region the centuries. While the artefacts of the ‘Stans’ more recent Soviet legacy are often more immediately apparent to visitors – Lenin statues, the Pamir Highwayand monuments to the former reach of the Aral Sea – echoes of Central Asia’s Persian roots are sometimes less obvious.

Kok-boru is the traditional sport of Nowruz © Anadolu Agency / Getty Images

Kok-boru is the traditional sport of Nowruz © Anadolu Agency / Getty Images

Disallowed as a religious observance during the Soviet era, Nowruz has re-emerged in force since 1991 as the cultures of the region have re-engaged with their ancient roots. As Central Asia looks towards spring each March, Nowruz marks the turning point at which the worst of winter has passed and the start of a new year means the return of warmth and life to the countryside.

Nowruz food and drink

Sumalak, a thick wheat-based beverage, is typically drunk during Nowruz © Stephen Lioy / Lonely Planet

Sumalak, a thick wheat-based beverage, is typically drunk during Nowruz © Stephen Lioy / Lonely Planet

From capital cities to remote villages, the holiday is marked in much the same way throughout the ‘Stans. For many days before 20 March, the women of each household clean and cook and prepare for the new year. Sumalak (Sümölök; Сумолок in Kyrgyz), a wheat-based beverage, shows up on the streets this one day each year. The wheat is soaked in water for a week until it sprouts, and it has to be cooked for a full day with sugar, flour and oil. Dark, grainy, earthy, thick…it’s the kind of thing you want to drink exactly once a year.

A Nowruz dinner table is traditionally laid out with seven items, all beginning with the Arabic sound ‘sh’ – sharob (wine), shir (milk), shirinliklar (sweets), shakar (sugar), sharbat (sherbet), sham (a candle) and shona (a new bud). The candles are a throwback to pre-Islamic traditions and the new bud symbolises the renewal of life.

Nowruz sport: kok-boru

For locals and tourists alike, Nowruz is also often an excuse to get out and watch kok-boru. Known originally as buzkashi (a Persian phrase meaning ‘goat dragging’), the name of the game varies from country to country but the chief objective is the same: a team of horsemen carry a goat carcass to a large goal at the end of a playing field while preventing a competing team from doing the same. Though deeply traditional, some visitors understandably may find the sport unsettling or even gruesome.

Kok-boru and other equestrian sports are popular throughout the ‘Stans during Nowruz © Stephen Lioy / Lonely Planet

Kok-boru and other equestrian sports are popular throughout the ‘Stans during Nowruz © Stephen Lioy / Lonely Planet

The rules of the game sound simple, but the crashing of twenty fierce riders who are attempting the already significant challenge of dragging a whole goat from ground to horseback to goal is an event meriting the furore of the large crowds that gather to watch. Add in large sums of cash and prizes like new cars, and it becomes a local focal point of the holiday season.

Nowruz customs

Nowruz is a day to spend with family, visit friends and neighbours, and maybe show off a bit; the kind of day to dress up in your finest clothes and your nicest hat and head out to socialise.

Family and food: two important components of Nowruz in Central Asia © VYACHESLAV OSELEDKO/AFP/Getty Images

Family and food: two important components of Nowruz in Central Asia © VYACHESLAV OSELEDKO/AFP/Getty Images

Whether sipping on sumolok with the neighbours, sharing meat skewers with friends or joining the stadium crowds to cheer on horsemen from across the country, in Central Asia Nowruz is a day to be out and about, celebrating spring’s warmth even if the last snows of winter still linger on the streets and hills.

With the horse games finished on the morning of 21 March, in village fields and capital city stadiums, the mostly-male kok-boru audiences trickle back into town centres to rejoin family celebrations. In Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan, as traffic is rerouted around the central square and boisterous midday dance troupes give way to early evening pop stars, yurt tents erected for Nowruz keep waitresses busy passing out cup after cup of tea.